By: Shashank Upadhye

Introduction

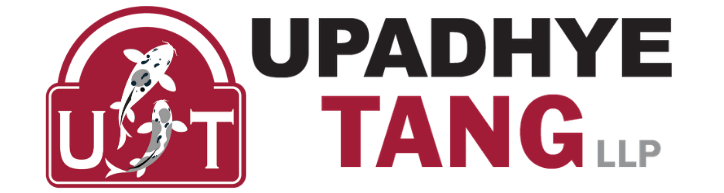

Typically, patent infringement requires comparing the patent claims to the accused device or process. Patent claims are stylized differently but the import is the same; there must be some correspondence between what is claimed compared to the accused device or process. A simplistic way is to envision a so-called claim chart, in which column 1 of the chart lists out the patent claim limitations and column 2 identifies the parts, pieces, components, or ingredients in the accused device. Here is a sample claim chart (claiming my dog):

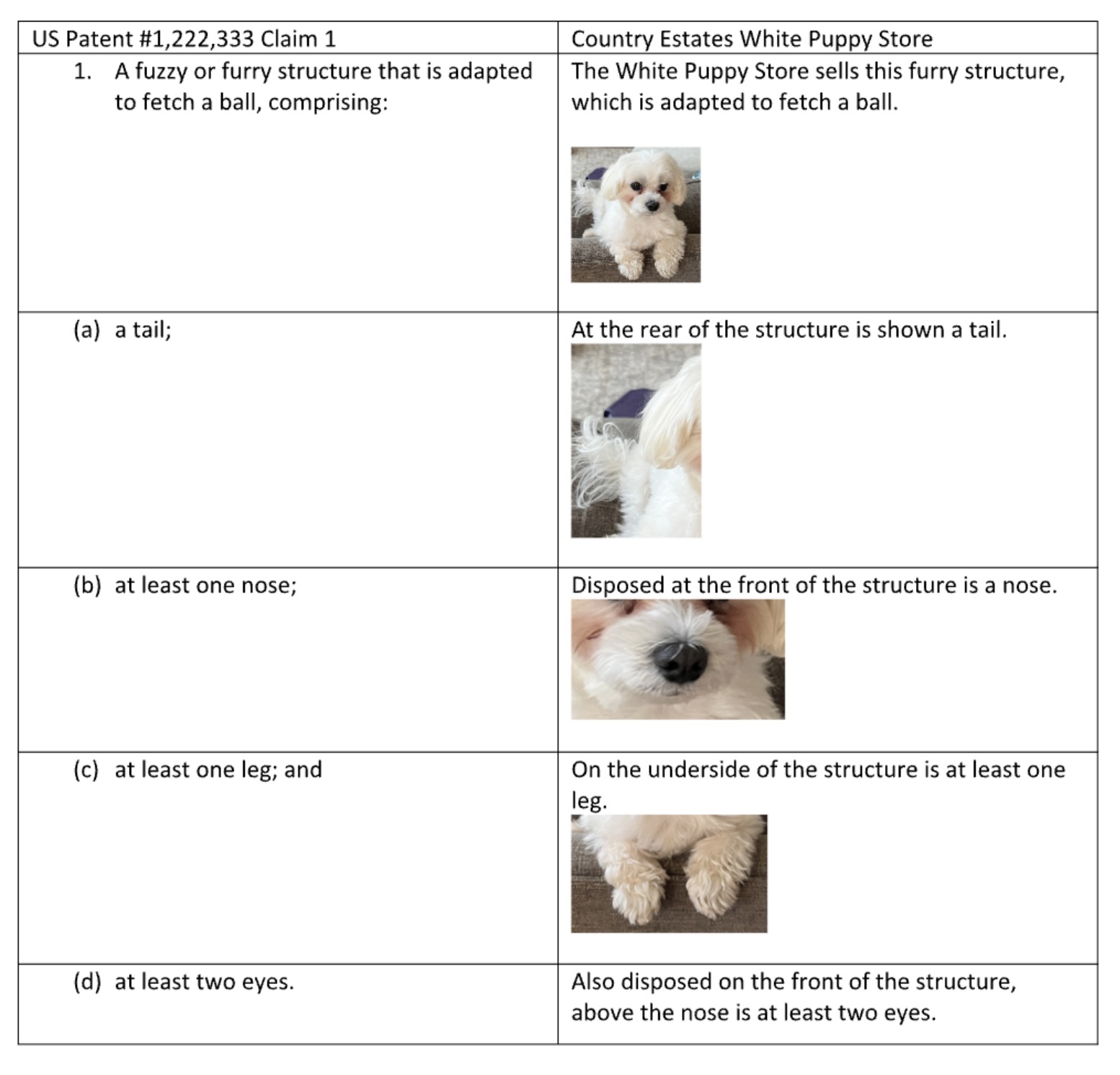

Now what happens if the claim recites different items, called claim limitations, but the accused device does not expressly have it? Patentees will try to argue that perhaps a single part/piece/component or ingredient can satisfy different claim limitations. Here is an example where the patentee asserts that the Orange Juice in the accused children’s drug product can satisfy both the citric acid limitation and the orange flavor limitation. Is this permissible?

Proving Infringement When One Element Satisfies Two Claim Limitations (The Doctrine of Double Inclusion)

In these situations, the rules of proving patent infringement remain the same. There is nothing magical about this type of patent infringement proof. Step 1 of the infringement analysis is claim construction and therein lies the rub!

The patentee will argue that the formulation claim does not require a one-to-one correspondence to unique ingredients. The patentee will argue that there is no “separateness” of elements required, and that “duality” is permissible. So, it is permissible that the Orange Juice is both a citric acid stabilizer and the flavoring agent at the same time. The defendant would argue that the single ingredient Orange Juice can be either the flavor agent or the stabilizer, but not both at the same time. That is, how can some molecules of the juice act like a stabilizer and other molecules of the juice be the flavor agent? And with other patent law doctrines including the word “double” (like double patenting or double inclusion), one can coin this situation as the doctrine of double counting.

The first step in the process is to construe the claim, via claim construction. The Supreme Court in Teva vs Sandoz, 574 U.S. 318 (2015) stated that construction requires the traditional tools, such as the claim language itself, the claim structure, then resort to intrinsic evidence (such as the patent specification, the prosecution history). Claim construction tools are described in Shashank Upadhye, Generic Pharmaceutical Patent and FDA Law, 15 th Ed. (2024-2025), Chapter 15 (available on the Thomson Reuters bookstore here: https://shorturl.at/0UWA7).

In this example, one can look at the structure of the claim itself. First, it uses separated subheadings like “(a)”, “(b)”, “(c)” and “(d)”. That indicates that the patentee intended to separate the limitations. Then the ingredients are listed separately (irrespective of whether the (a), (b), (c), (d) subheadings were used). That is again evidence that there is separateness.

The Federal Circuit has held that when claim limitations are separately listed, there is a presumption that the components are distinct. See, Kyocera Senco Industrial Tools Inc. v. International Trade Commission, 22 F.4th 1369, 1382 (Fed. Cir. 2022)(“There is, therefore, a presumption that those components are distinct.”(citing to Becton, Dickinson & Co. v. Tyco Healthcare Grp., LP, 616 F.3d 1249, 1254 (Fed. Cir. 2010). Despite the presumption of separateness, the Federal Circuit has also stated that such a rule is not per se. Rather, one must still complete the construction analysis rubric to see if the presumption is rebutted, for example, by the other intrinsic evidence. See also, Google LLC v. EcoFactor, Inc., 92 F.4th 1049, 1058 (Fed. Cir. 2024)(“Rather, we have explained that there is a “presumption” that separately listed claim limitations may indicate separate and distinct physical structure, but that presumption may always be rebutted in the context of a particular patent.”).

The next step in the separate versus duality inquiry is to look at the other intrinsic evidence. That includes looking at the patent specification itself. First the court will review whether there is express language indicating that the patentee intended (or expressed) that separately listed elements can be satisfied by a single component. See, Sun Pharma v. Saptalis Pharm., 2019 WL 2549267, at *7 (D. Del. June 19, 2019; docket #18-cv-648)); Otsuka Pharma v. Mylan, 2023 WL 5928313, at *3 (D. Del. Sept. 12, 2023; docket #22-cv-464). Then a court may look to see if the claim construction would render the claim nonsensical or render a term superfluous, because a court should not, where possible, render a claim term superfluous. See, Digital Vending Serv. v. Univ. of Phoenix, 672 F.3d 1270, 1275 (Fed. Cir. 2012). As is typical in pharmaceutical formulation claims, there often quantitative amounts recited in specific units of measurement. In arguing for duality, would it render measurements and units of measurements meaningless? For example, if one claim limitation measures in mass and the other claim limitation measures in volume, would treating the same element in the accused formulation be meaningless because the accused ingredient just can’t be in both mass and volume at the same time?

Another tool is to see if the claim limitations are in distinct paragraphs in the specification. For example, one ingredient may be in a paragraph distinctly related to flavoring agents, such as: “flavorants may include those flavors known to the skilled artisan, such as natural and artificial flavors. These flavorings may be chosen from synthetic flavor oils and flavoring aromatics and/or oils, oleoresins and extracts derived from plants, leaves, flowers, fruits, and so forth, and combinations thereof. Also useful flavorings are artificial, natural and synthetic fruit flavors such as vanilla, and citrus oils including lemon, orange, lime, grapefruit, yazu, sudachi, and fruit essences including apple, pear, peach, grape, blueberry, strawberry, raspberry, cherry, plum, pineapple, apricot, banana, melon, apricot, cherry, raspberry, blackberry, tropical fruit, mango, mangosteen, pomegranate, papaya and so forth.”

And suppose the specification describes the stabilizers as including various acids expressly reciting citric acid as an example of a stabilizer. For example, it may say, “examples of suitable acids capable of stabilizing the formulation include, but are not limited to, malic acid, citric acid, ascorbic acid, tartaric acid, adipic acid, lactic acid, furmaric acid, maleic acid, acetic acid, phosphoric acid, or salts thereof.” In this example, the patent expressly discusses citric acid as a stabilizer.

Next, the Court may look to the various examples set out in typical pharmaceutical formulation patents. If there are multiple examples where the patentee states that the various embodiments have stabilizers and flavors, this is again evidence that the pattern of examples show separateness, not duality. See, Kraft Foods v. International Trading, 203 F.3d 1362, 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2000). Equally, the absence of any example showing duality of the ingredient is important.

The patentee may resort to the deafening silence of any duality by resorting to typical generic boilerplate language at the end of the patent text. But boilerplate language is generally not sufficient to overcome the presumption of separateness. See, D. Three Enter. v. SunModo, 890 F.3d 1042, 1051 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

The patent specification is not the only source of intrinsic evidence, though it is a powerful source. One ought to view the prosecution history also. For example, suppose the claim started broadly claiming the citric acid stabilizer, but was rejected. The patentee then amended the claim to add the separate orange flavor agent and the claim was then allowed. Accordingly, that is strong evidence that the orange flavor agent is different from the citric acid stabilizer, and hence separate. Similarly, the prosecution history may contain patentee arguments that discuss the claims, the amendments, the prior art, and the rejections. Those statements are indicative of the separateness or duality argument.

Finally, the patentee may argue that extrinsic evidence may show duality by resort to literature or experts. Extrinsic evidence is less reliable than intrinsic evidence because it is generally untethered from the patent-in-suit. See, Genuine Enabling Technology LLC v. Nintendo Co., Ltd., 29 F.4th 1365, 1372–73 (Fed. Cir. 2022)(“Extrinsic sources might not have been written for the purpose of illuminating the scope of the patent at issue; they might have been written for an audience different from persons of ordinary skill in the art; they might suffer from litigation bias; and relatedly, they might have been selectively plucked from the unbounded universe of potentially relevant material to advance a litigant’s position. We have therefore cautioned against “undue reliance” on extrinsic evidence because it “poses the risk that it will be used to change the meaning of claims in derogation of the indisputable public records consisting of the claims, the specification and the prosecution history, thereby undermining the public notice function of patents.” In other words, extrinsic evidence is to be used for the court’s understanding of the patent, not for the purpose of varying or contradicting the terms of the claims.”). So, the court may need to guard against random descriptions in the literature how an ingredient “may” or “might” behave or be used that is divorced from the context of the patent-in-suit.

Expert testimony also helps divine the intent, but like all extrinsic evidence, it should be used to enlighten, but not contradict the intrinsic evidence. See, Genuine Enabling Technology LLC v. Nintendo Co., Ltd., 29 F.4th 1365, 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2022)(“However, expert testimony may not be used to diverge significantly from the intrinsic record. A court should discount any expert testimony that is clearly at odds with the claim construction mandated by the claims themselves, the written description, and the prosecution history, in other words, with the written record of the patent. Expert testimony may not be used to vary or contradict the claim language. Nor may it contradict the import of other parts of the specification.”). Also, given the implicit nature of experts in litigation, each party will proffer an expert that will testify in a favorable manner to that party.

In the end, claim construction can often be dispositive to the infringement issue. It is important to resolve the claim construction issues early.

Practical Tips For Patentees

Many patent prosecutors are not heavily involved in patent litigation. Accordingly, they are not fully aware of how a claim may be litigated nor how courts construe claims. To this end, in the pharmaceutical context, prosecutors should review how certain elements are characterized in the text itself, how amendments to the claims are made, scrutinize arguments made, and then also review pending applications (and office action responses) with skilled litigation counsel.

How we can help you?

Our firm specializes in patent strategy and litigation. We help clients analyze the portfolio of patents. For investors, we provide the deep dive due diligence to find any problems in the patent portfolio or vet out the accuracy of pitch-decks. We help clients in patent litigation, appeals, counseling, opinions of counsel, and PTAB proceedings. When your current firm needs help or the client needs a change of counsel, we can help.

About Upadhye Tang LLP

Upadhye Tang LLP is an IP and FDA boutique firm concentrating on the pharmaceutical, life sciences, and medical device spaces. We help clients with navigating the legal landscape by helping on counseling and litigation. Clients call us to help move drug and device approvals along and to represent them in IP and commercial litigation. Call Shashank Upadhye, 312-327-3326, or by email: shashank@ipfdalaw.com, for more information.

No Attorney-Client Relationship or Legal Advice

The content of this website has been prepared by Upadhye Tang LLP for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Nothing shall not be construed as an offer to represent you, nor is it intended to create, nor shall the receipt of such information constitute, an attorney-client relationship. Please call us first with any questions about the firm.

Nobody should take any action or choose not to take any action based upon the information on this website without first seeking appropriate professional counsel from an attorney licensed in the user’s jurisdiction. Because the content of any unsolicited Internet email sent to Upadhye Tang LLP at any of the email addresses set forth in this website will not create an attorney-client relationship and will not be treated as confidential, you should not send us information until you speak to one of our lawyers and get authorization to send that information to us.

Individual Opinions

The opinions and views expressed on or through this website, or any newsletter, are the opinions of the designated authors only, and do not reflect the opinions or views of any of their clients or law firms or the opinions or views of any other individual. And nothing said in any newsletter or website reflects any binding admission or authority.