Typically, brand and generic drugs stay nicely in their own lanes. The consuming public generally knows when the drug taken is branded or generic. But are there times when a generic drug may become a branded drug, whether unintentionally or intentionally? And when we say a branded drug in this context, we do not mean that the underlying generic drug approval (the ANDA) is converted into a branded drug approval, rather the approvals remain the same. But the market effect or the FDA considers a certain generic drug product to be the equivalent of a branded drug.

FDA Designates ANDA Product as New Reference Listed Drug (RLD)

Many times, after the market is punctuated with many generic drug products, the original brand company will withdraw the branded product from the market. After all, there is no need to engage in the typical branded drug marketing strategies, such as advertising, marketing, detailing to physicians, and then also keep updating FDA on pharmacovigilance. In other words, from the brand company perspective, maintaining branded drug activities for a trickle of residual brand sales doesn’t make much sense. But when the brand company withdraws its product, then FDA needs to designate another marketed drug as the reference listed drug for new generic entrants to run the BE studies.

ANDA sponsors would be surprised to learn that its ANDA has now been nominated as the RLD. The ANDA RLD now is tasked with ensuring label updates are done. And being denominated as the RLD may subject that ANDA sponsor to the class action lawsuits on failure to warn. A discussion of the defenses the ANDA sponsor has against any product liability failure to warn lawsuits is beyond the scope of this article. But in sum, one way for an ANDA drug product to be considered a branded drug is when the FDA says so.

Generic Drug Competitors Shrink Creating Increasing Market Share

Generic drug companies operate in a hypercompetitive, low margin market. Generic companies come in myriad forms, such as global sized companies that have immense infrastructures, costs, and thus must operate in high volume high profit markets. Whereas other companies can be small, operate in razor thin margins, yet still survive. Contrary to popular belief, generic drug prices are very low because in a typical market, the prices race down the toilet quickly. And when the market it too hypercompetitive and profit margins disappear and become unprofitable, a generic drug company may flush whatever plans it has left to compete, and wash its hands of the market and exit. So as a 10-competitor market shrinks to 3-4 competitors, those survivors tend to increase their relative market shares, and that increase may increase profits. So, in concept, there are times when the multisource market devolves into one player remaining because everyone else just left. The sole survivor can reap the reward of 100% market share and any price increases that the market will tolerate.

Generic Drug Company Enforcement of Patents To Create A Branded Drug Market

Typically, one does not expect a generic drug company to have an enforceable patent that is sufficient to drive all competitors off the market, to thereby create a monopoly. But when it does, it can be a windfall for a generic drug company. A generic company that is first to develop a generic version to a complex branded drug may have developed inventive techniques or formulations to solve a technical problem. That is, the generic company may have figured out how to make the generic version, how to do innovative testing for characterization and qualification purposes, how to show sameness, etc. And having one or more patents on those innovations, though being developed by the generic company, are still valuable. A later generic company may be unable to develop its own generic version because the first generic company’s patents.

A recent case explains how a generic company has ostensibly solved a problem and obtained patents. If the overall strategy (of which I am completely guessing) is successful, it may be that the generic company will become the new sole product, and the patents may even block the original branded drug from reentering the market.

Pfizer owns the Chantix® drug product for anti-smoking/smoking cessation. It made Pfizer about a billion dollars per year. Par launched the first generic version of it back in Sept. 2021. [note 1] However, the varenicline molecule was one identified as being prone to “nitrosamine” impurity formation. Nitrosamines can be cancer-causing. In another drug product, the FDA determined that the “sartans” (which are hypertension drugs) were prone to nitrosamine formation and FDA required drug makers to recall the products and control for nitrosamine formation, then re-launch (if they could reduce the impurities). That caused a big shortage among patients.

So too here FDA identified the varenicline tendency to form nitrosamines and many drug makers, including Pfizer [note 2], pulled their products off the market. Apotex had a Canadian varenicline that ostensibly had the low-impurity, and in July 2021 FDA allowed Apotex to specially import its Canadian version into the US to help ease the US drug shortage [note 3]. To help consumers, FDA also did its own testing in Aug. 2021 to show which product had what levels of impurity [note 3]. Par’s ANDA 20-1785 was filed on May 10, 2010 and approved Aug. 11, 2021 (yes, 11 year later). Zydus got ANDA approval on June 12, 2023 and announced it would launch thereafter.

Par obtained US patent no. 11,717, 524 on Aug. 8, 2023. The same day, Par sued Zydus (DEL docket no. 23-cv-00866). The patent chains its earliest filing date to March 11, 2022.

Par also obtained a patent on a formulation containing maltodextrin (US Patent No. 11,602,537) but did not sue Zydus. Presumably it’s because Zydus doesn’t have maltodextrin in its formulation.

The Patent Issues

First and foremost, Par filed the lawsuit and filed a TRO/PI/request for expedited discovery. The expedited discovery, among other things, probably requested the nitty gritty details of the Zydus manufacturing process as Par says in the complaint, it doesn’t have these details. Judge Andrews, who is set go senior status in Dec. 2023, denied the TRO on Aug. 9th, but deferred the PI and discovery to the magistrate.

The Par vs. Zydus case will raise several interesting patent issues. First, Zydus presumably makes its formulation in India and imports only the final dosage form tablet. Therefore, the Method claims of the ‘524 are not likely directly infringed in the USA. Par will have to make the case that the importation infringes under Section 271(g), though Section 271(g) is not often litigated. It requires proof that the patented process was done in the ex-USA country but also that the product that is imported is not materially changed. In other words, it will require the court to delve into what is the product made by the patented process and is that product the same as that is imported? Or if the product that is imported is different, is it materially changed by subsequent processes? Typically, patented methods of manufacturing relate to the manufacture of the API and the product imported is the finished dosage form. Here, though, the patented method of manufacture is to the final tablet form.

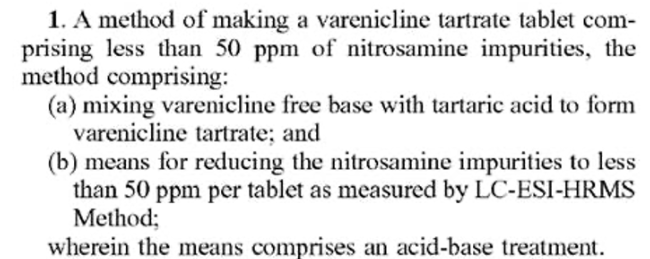

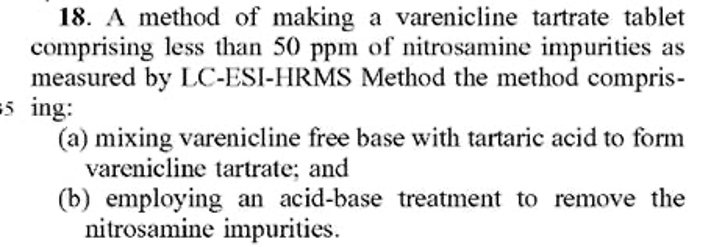

Another issue is how to construe claim 1, which is clearly a “means for” format. Under “old” patent law, means plus function claims were governed under old Section 112, paragraph 6. After the AIA, it is now Section 112(f). Means plus function claims, or here step plus function claims, have been treated differently in claim constructions. The constructions tend to hone more directly on the “means” or “steps” and the corresponding acts/materials/acts, thereof. If the court construes the step for narrowly, perhaps Zydus can escape if it doesn’t do that step in the same way as Par’s way.

Further, if the ‘524 patent was filed as early as March 2022, will Zydus argue that the low-impurity forms are obvious, and hence invalid. In obviousness cases, there is often an attack on the motivation/suggestion/teaching to combine. Yet here, FDA was requiring drug sponsors to clean up the nitrosamines. Long before March 2022, companies were doing it. Is FDA guidance enough of a motivation? Are the known nitrosamine clean-ups by others in other drug products enough M/S/T to clean up varenicline? Of course, the devil is in the details and the prior art, but the Par v. Zydus case may discuss the issues of what role FDA guidances have in motivating drug sponsors to take certain actions.

The Monetary Issues

Imagine that Par could successfully assert this patent against every ANDA sponsor and even Pfizer’s own Chantix (if Pfizer cleaned up its Chantix and relaunched it). Par’s generic version could become the only product and Par could price the product like a new brand product. It was a billion-dollar product for Pfizer after all. On the other hand, if the patent is only assertable against a few, but not all, ANDA sponsors, then presumably those other sponsors will stay on the market. Is there a point for Par to assert a patent against one sponsor, remove that one product from the market, but others stay on? The others benefit too from Par’s assertion of the patent. For Par, any monetary damages would be based on the patent issuance date thereafter even though Zydus had launched in June 2023.

How we can help you?

We help clients in patent litigation, appeals, counseling, opinions of counsel, and PTAB proceedings. When your current firm needs help or the client needs a change of counsel, we can help.

About Upadhye Tang LLP

Upadhye Tang LLP is an IP and FDA boutique firm concentrating on the pharmaceutical, life sciences, and medical device spaces. We help clients with navigating the legal landscape by helping on counseling and litigation. Clients call us to help move drug and device approvals along and to represent them in IP and commercial litigation. Call Shashank Upadhye, 312-327-3326, or by email: shashank@ipfdalaw.com, for more information. Read more about our firm at www.ipfdalaw.com.

No Attorney-Client Relationship or Legal Advice

The content of this website has been prepared by Upadhye Tang LLP for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Nothing shall not be construed as an offer to represent you, nor is it intended to create, nor shall the receipt of such information constitute, an attorney-client relationship. Please call us first with any questions about the firm.

Nobody should not take any action or choose not to take any action based upon the information on this website without first seeking appropriate professional counsel from an attorney licensed in the user’s jurisdiction. Because the content of any unsolicited Internet email sent to Upadhye Tang LLP at any of the email addresses set forth in this website will not create an attorney-client relationship and will not be treated as confidential, you should not send us information until you speak to one of our lawyers and get authorization to send that information to us.

Individual Opinions

The opinions and views expressed on or through this website, or any newsletter, are the opinions of the designated authors only, and do not reflect the opinions or views of any of their clients or law firms or the opinions or views of any other individual. And nothing said in any newsletter or website reflects any binding admission or authority.